Insights | 02 December 2025

Swiss Supreme Court Clarifies Bank Liability in fraudulent Payment Instructions case (Decision 4A_577/2024)

The Swiss Supreme Court has rendered a significant decision on the liability of banks in cases involving disputed payment instructions on joint accounts. The judgment addresses key contractual clauses commonly found in banking relationships, including risk-transfer provisions, approval and delivery presumptions, and the scope of a bank’s duty of care.

I. Background

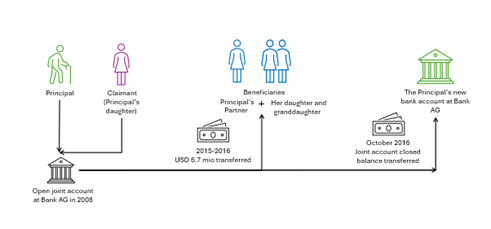

In 2008, a joint account relationship was established at the Zurich branch of a Swiss bank by an elderly account holder (the principal) and his daughter (the claimant). The accounts included USD and EUR sub-accounts and were structured as “either/or” accounts, allowing each holder to issue instructions independently.

The account opening documentation included:

- A hold mail correspondence declaration, combined with a delivery presumption and approval presumption.

- A risk-transfer clause shifting liability for losses due to forged instructions to the client, unless the bank acted with gross negligence.

- A clause on lack of capacity to act, allocating related risks to the client unless officially notified.

Between 2015 and 2016, approximately USD 6.7 million was transferred from the joint accounts to beneficiaries connected to the principal’s partner – as well as the partner’s daughter and granddaughter. In October 2016, the joint accounts were closed and remaining funds transferred to an account solely in the principal’s name.

The claimant – i.e., the principal’s daughter and joint account holder – did not verify the hold mail correspondence and raised no objections until 2018, when she discovered the account closure.

In 2021, the claimant sued the bank before the Zurich Commercial Court, asserting a performance claim for restitution of funds, arguing that the transfers and account closure lacked valid instructions.

The Zurich Commercial Court partially upheld the claim regarding a USD 3.5 million transfer on 7 September 2016. It found that the bank was unable to prove a valid instruction and had acted with gross negligence, so could not therefore rely on the risk-transfer or approval presumptions. This claim was reduced by one-third due to contributory negligence.

The bank appealed to the Swiss Supreme Court.

II. Key Issues and Supreme Court Findings

The Swiss Supreme Court dismissed the bank’s appeal and confirmed the Zurich Commercial Court’s judgment based on the following key considerations:

- Performance claim vs. damages claim: the Swiss Supreme Court reaffirmed its established practice that in cases of disputed payment instructions (e.g., alleged forgeries), the client may pursue a performance claim (i.e. restitution of the deposited funds) rather than being limited to a damages claim.

- Three-step analysis for bank liability: The Swiss Supreme Court also reaffirmed that cases related to bank transfers that were made by the bank (allegedly) without a valid instruction by the client must be examined in three steps:

- Step 1: it must be determined whether the transactions were based on valid instructions or whether they were subsequently approved by the client. Delivery presumptions and ratification, often included in banks’ general terms and conditions, apply only if the client could reasonably detect irregularities. Where correspondence is held by the bank, Swiss courts consider that the client cannot be deemed to have accepted/ratified fraudulent transfers.

- Step 2: if no valid instruction exists, the next step is to examine whether a contractual risk-transfer clause shifts liability to the client. Such clauses cannot be invoked where the bank acted with gross negligence.

- Step 3: it must be considered whether the bank has a counterclaim for damages against the client due to contributory fault, which it could off-set against the performance claim.

- Gross negligence and risk-transfer clause: In the case at hand, the Swiss Supreme Court upheld the Zurich Commercial Court’s finding of gross negligence by the bank regarding the USD 3.5 million transfer, the instruction for which was allegedly signed by the principal. The bank failed to verify the instruction with the principal. It did verify the instruction with the principal’s partner (the beneficiary’s mother) – who was not the account holder – and this was done despite several red flags:

- unusual transaction size (compared with prior transfers);

- computer-generated instruction (supposedly signed by the principal), suggesting possible third-party involvement;

- discrepancies in the signature compared with account-opening documents; and

- contradiction with a prior instruction to close the account.

- Delivery presumptions and ratification: The court confirmed that these presumptions apply only if the client could reasonably detect irregularities. In this case, the claimant’s failure to consult hold mail correspondence constituted minor negligence, but did not absolve the bank of its gross negligence.

Contributory negligence: The claimant’s limited monitoring of hold mail correspondence justified a one-third reduction of her claim.

III. Implications for banks and clients

This judgment reinforces and clarifies several principles of Swiss banking law:

- Heightened scrutiny for unusual transactions: banks must exercise particular care when instructions involve unusually high sums, deviate from prior patterns, or present irregularities (typed instructions, signature discrepancies). Reliance on proxies or related beneficiaries for confirmation is insufficient.

- Risk-transfer clauses are not absolute: standard general terms and conditions clauses shifting the risk of forgery to clients will not protect banks where gross negligence is established.

- Shared responsibility: clients remain under a duty to monitor account documentation. Failure to do so may reduce recovery.

Back to listing